CASE 1

CLINICAL DATA:

A man presented with chronic cough. Occasional haemoptysis. No previous illness before.

Mantoux test – indurated area of 24mm.

CHEST RADIOGRAPH:

- Small cavitations in the left upper lobe with fibrosis and nodular opacities.

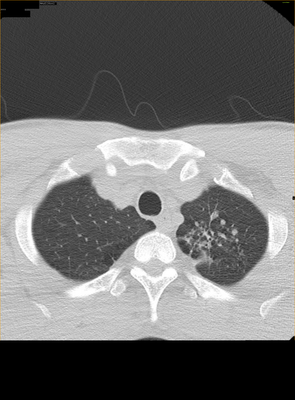

HRCT THORAX:

Fibrosis and small lung cavitations in the left upper lobe.

CASE 2:

A 47 year-old man with chronic cough. Poorly controlled DM status.

Chest radiograph:

- Cavitating pneumonia of left upper lobe.

Sputum AFB direct smear is positive.

CASE 3

CLINICAL DATA: A 29 year-old lady with persistent cough for 1month. Delivered a baby 3 month ago. History of contact with pulmonary TB.

CHEST RADIOGRAPH:

Reticulo-nodular opacities in both upper lobes (right > left) with minimal fibrosis in right lung apex.

Sputum AFB: positive.

CASE 4

CLINICAL DATA:

A 52 years-old gentleman with underlying DM. Presented with cough and fever for 2months duration. Admitted to hospital for haemoptysis.

Previous screening CT THORAX 2 years ago showed a homogenous solid mass in superior segment of left lower lobe presuming to be lung hamartoma (images not available).

HbA1C: 11.6%

ESR 57mm/hour.

CHEST RADIOGRAPH:

- A cavitating lung lesion in the superior segment of left lower lobe.

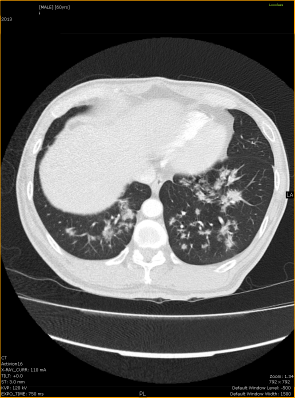

CONTRAST ENHANCED CT THORAX:

The previously seen solid lung lesion (presume to be lung hamartoma) in superior segment of left lower lobe showed cavitation. It is measuring 4.6cm x 2.7cm in size.This lesion is representing lung tuberculoma.

There is tree-in-buds appearance adjacent to the cavitating lung lesion.

SPUTUM: AFB 3+

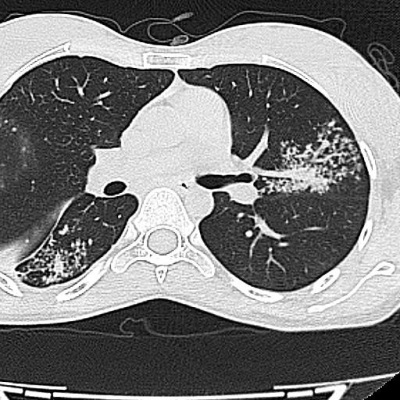

CASE 5

CLINICAL DATA: A 60 years old man of poorly controlled diabetis mellitus presented with cough.No fever. No loss of appetite or loss of weight.

CHEST RADIOGRAPH:

- Multiple lung nodules of varying sizes predominantly in lower and mid lung fields.

- Patchy consolidation in the right upper lobe.

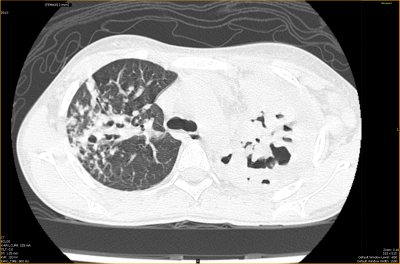

CT THORAX:

- Lung consolidation in right upper lobe.

- Cavitating lung lesion in left upper lobe.

- Nodular opacities in both lower lobes.

- Tree-in-buds in superior segment of left lower lobe.

Spiculated multiple lung nodules in both lower lobes. Some appearing as flame-shaped lung lesions.

SPUTUM: AFB 3+.

CASE 6

CLINICAL DATA: A 14-years old girl presented with chronic cough. Patient is underweight and pale looking. Enlarged left neck, left supraclavicular and left axillary nodes.

CHEST X-RAY:

- Consolidation of left lung with nodular opacities.

- Left hydropneumothorax.

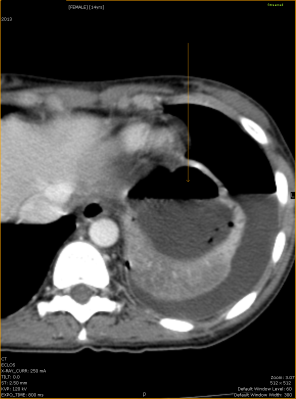

CT THORAX:

- Cavitation consolidation of left lung. Lung abscess in left lower lobe. Left hydronpneumothorax.

- Patchy consolidation in right upper lobe with tree-in-buds appearance.

- Peripheral enhancing with low center density enlarged nodes in the left neck, left supravlavicular, left axillary region and mediastinum.

- Cavitation lung consolidation in left lung.

- Lung abscess in left lower lobe.

- Left hydropneumothorax.

SPUTUM: AFB strongly positive.

CASE 7

CLINICAL DATA: A 29-yr-old lady presented with shortness of breath and hoarseness of voice.

Total White – normal.

ESR 26mm/hr (1-20)

Weight: 35.8 Kg

INVESTIGATIONS:

CHEST X-RAY:

- Nodular consolidation in bilateral lung fields.

- Thickened right lung fissure.

- A non spiculated lung nodule in the right upper lobe favouring lung granuloma.

- Tree-in-buds involving predominantly superior segment right upper lobe and anterior-lingular segment left lower lobe.

- Thickened adjacent lung fissures.

- Patchy lung consolidation.

TB quantiferon posiitive.

Sputum culture: Mycobactrium TB positive.

DISCUSSION:

Types of TB infection:

1. Primary TB .

- lungs are the primary organ of spread- accounting for about 70% of cases (1).

- extrapulmonary infection generally occurs as a result of hematogenous dissemination from a clinically occult pulmonary focus (1).

- typically a self-limited infection.

- about 5% of adults and up to 60% of infected children are asymptomatic (2).

- in a less competent host, the infection is walled off, but the bacillus remains viable, but dormant for many years (3).

- typically presents as a segmental or lobar consolidation usually involving the lower lobes (although any lobe may be involved) and the appearance is often indistinguishable from bacterial pneumonia (4).

- Inhaled bacteria are deposited in the mid and/or lower lung. The bacteria then undergo intracellular multiplication with lymphatic and hematogenous spread. Bacteria survive in areas of the lung with high oxygen content.

- multifocal involvement is seen in 12-24% of cases (5).

- prevalence of lymphadenopathy is greatest in the pediatric age group (about 90-96% of affected children (4,6,7) and is seen in about 43% of adults (4).

- Lymph node enlargement is a common finding with primary tuberculosis. This may occur with or without an upper lobe granuloma.

- Pleural effusion is found in up to 40% of adults, but only 5-10% of children with primary infection (7). Pleural fluid cultures are positive in only 20-40% of cases (pleural biopsy cultures are positive in 65-75% of cases) (5). Pleural effusion can be the only radiographic finding indicative of primary TB infection in about 5% of cases (5,7).

- Regression of radiographic findings is a slow process- requiring from 6 months to 2 years for resolution.

- Radiographic differentiation between active and inactive disease can only be made reliably on the basis of temporal evolution. The American Tuberculosis Association requires that a radiograph remain unchanged for a period of 6 months to indicate stable/inactive disease (8).

- Computed tomography can detect the presence of adenopathy, parenchymal consolidations, or evidence of endobronchial spread not seen on plain film radiographs. A normal chest radiograph has a high negative predictive value for the presence of active TB (5).

- Common findings of infection in infants include mediastinal and hilar adenopathy (seen in 90-95% of cases (3). The adenopathy is usually unilateral and located in the hilum or paratracheal region (3). On CT the nodes demonstrate central necrosis with rim enhancement (3).

- Pulmonary tuberculosis can manifest as pulmonary nodules mimicking lung metastasis.

2. Miliary (disseminated) TB.

- Typical miliary lesions may not be visible for 3 to 6 weeks after hematogenous dissemination (9).

- CXR reveals micronodular densities (1-2mm) diffusely throughout both lungs.

- HRCT demonstrates a combination of sharp and poorly defined 1 to 3 mm nodules distributed throughout the lungs and have no relationship to the airways in their distribution. The nodules usually resolve within 2-6 months with treatment (4).

3. Progressive primary TB.

- Widespread pulmonary infection due to impaired host immunity.

4. Reactivation or post-primary TB.

- Reactivation infection usually develops in the apical/posterior segments of the upper lobes (83-85% of cases) or superior segment of the lower lobes (11-14% of cases) (2).

- Patchy alveolar infiltrate. The cavities typically have thick, irregular walls which become smooth and thin with successful treatment (4).

- Hilar or mediastinal adenopathy is unusual in reactivation TB.

- An effusion may be the sole manifestation of reactivation TB (3).

- In addition to an upper lobe granuloma, there are also typically satellite nodules which may coalesce and be able to be identified on chest x-ray.

- Tree-in-bud pattern opacities are another finding indicative of postprimary tuberculosis.

- Cavitation is indicative of active and transmissible disease.

5. Tuberculous airway disease

- CT of the chest during active infection will reveal irregular tracheobronchial narrowing and wall enhancement with I.V. contrast. The mediastinal fat around the trachea often demonstrates increased density consistent with inflammation.

6. Chronic tuberculous empyema

- On CXR there is usually a moderate to large loculated pleural fluid collection with pleural calcification and enlargement of the overlying ribs.

- CT demonstrates the loculated pleural fluid surrounded by a thick, calcified pleural rind (10).

7. Tuberculoma.

- Well defined or have irregular margins and mimic a lung neoplasm.

- Most lesions are less than 3 cm in size and calcification can be seen in 20-30% of cases (usually ndoular or diffuse).

- Small satellite nodules about the larger lesion can be found in up to 80% of cases.

- Tuberculoma seems to be round or polygonal shape and primary lung cancer is more likely to be lobulated shape. The smooth border nodule is found only in tuberculoma (27%) whereas 93% of primary lung cancer had spiculated border compared to 73% among tuberculoma (p < 0.05).

TB lymphadenitis:

- In patients with active tuberculosis, nodes larger than 2 cm in diameter commonly show central areas of low attenuation on contrast-enhanced CT, with peripheral rim enhancement

- The areas of relative low attenuation are not of water density, but range from about 40 to 60 HU; they are usually visible only on contrast-enhanced scans.

Tree-in-buds on HRCT LUNG:

- Tree-in-buds apperance in the lungs is usually visible on standard CT, however, it is best seen on HRCT.

- centrilobular nodules are 2-4 mm in diameter and peripheral, within 5 mm of pleural surface.

- The centrilobular nodules connection to opacified or thickened branching structures extends proximally (representing the dilated and opacified bronchioles or inflamed arterioles).

- Initially described in cases of endobronchial spread ofMycobacterium tuberculosis (11).

- subsequently been reported as a manifestation of a variety of entities, including peripheral airways diseases such as infection (bacterial, fungal, viral, or parasitic), congenital disorders, idiopathic disorders (obliterative bronchiolitis, panbronchiolitis), aspiration, inhalation, immunologic disorders, and connective tissue disorders and peripheral pulmonary vascular diseases such as neoplastic pulmonary emboli.

QuantiFERON-TB Gold:

- a simple blood test that aids in the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- unaffected by previous vaccination with Bacille-Calmette Guerin (BCG).

- a modern alternative to the tuberculin skin test (TST or Mantoux).

- highly specific and sensitive: a positive result is strongly predictive of true infection with M. tuberculosis.

- cannot distinguish between active tuberculosis disease and latent tuberculosis infection, and is intended for use with risk assessment, radiography, and other medical and diagnostic evaluations. Like any diagnostic aid, QFT cannot replace clinical judgement.

- measures the cell-mediated immune response (cytokines) to very specific TB antigens.

- performed by collecting whole blood (1 mL) into each of three blood collection tubes

References:

1. AJR 2010; Tan CH, et al. Tuberculosis: a benign impostor. 194: 555-561

2. Radiology 1999; Leung AN. Pulmonary tuberculosis: The essentials. 210: 307-322.

3. AJR 2008; Jeong YJ, Lee KS. Pulmonary tuberculosis: up-to-date imaging and management. 191: 834-844

4. Radiographics 2007; Burrill J, et al. Tuberculosis: a radiologic review. 27: 1255-1273

5. Radiology 1999; Leung AN. Pulmonary tuberculosis: The essentials. 210: 307-322

6. Society of Thoracic Radiology Annual Meeting 2000 Course Syllabus; Leung AN. Pulmonary tuberculosis. 83-84.

7. Radiol Clin N Am 2005; Tarver RD, et al. Radiology of community-acquired pneumonia. 43: 497-512.

8. AJR 1997; 168-1005-1009.

9. Society of Thoracic Radiology Annual Meeting 2000 Course Syllabus; Leung AN. Pulmonary tuberculosis. 83-84

10. Radiographics 2001; Kim Hy, et al. Thoracic sequelae and complications of tuberculosis. 21: 839-860.

11. ImJG, Itoh H, Shim YS, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis: CT findings—early active disease and sequential change with antituberculous therapy. Radiology1993; 186: 653–660